When Accenture went public in 2001, it was incorporated in Bermuda, where it joined a gaggle of crypto-American insurance companies. In 2009, proposed tax changes from the Obama administration encouraged the consultancy to re-incorporate in Ireland, where it was joined by Medtronic, Johnson Controls, and several pharmaceutical companies.

It is unclear how many of Accenture’s 721,000 employees consider Ireland home. Judging from the pharmaceutical and software profits booked in Ireland, it must be both the sickest and the most tech-savvy country on the planet.

Six of America’s biggest pharma companies recorded 90% of their profits overseas in 2022, despite the fact that the majority of their sales were in the US. And in 2020, a Microsoft subsidiary in Ireland reported profits of $315 billion – equal to three-quarters of Ireland’s GDP – despite the entity having no actual employees.

And then there is e-Estonia, a virtual jurisdiction where one can gain virtual citizenship for online businesses and draw on incorporation, banking, and payment systems – all without leaving the comfort of one’s laptop, wherever it happens to be.

It turns out that “law and custom” cannot slow down a company convinced of its duty to maximize profits. If you don’t like the law and custom where you are, it’s easy to relocate to a more congenial jurisdiction.

Big Business today

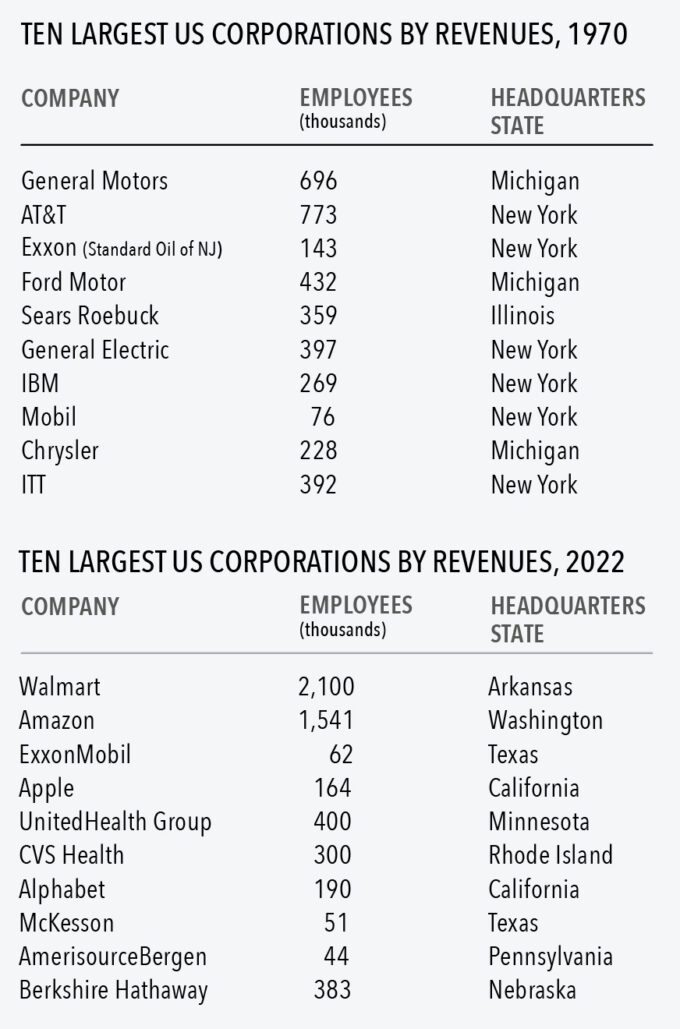

The biggest American businesses today bear little resemblance to the industrial giants that dominated the economy when Friedman wrote. Today’s enterprises are dispersed both geographically and organizationally. The 1970 cohort’s headquarters were concentrated in New York, Detroit, and Chicago – today’s group is scattered across the country. And while the Rouge plant employed 100,000 people, Apple’s retail stores average perhaps 100 staff each; a Walmart supercenter might have 350 workers, and an Amazon warehouse between 1,000 to 1,500. In contrast to the high wages and career-long employment of the 1970 group, retail work today is notable for its low pay and high turnover, with Amazon’s hourly workforce reportedly experiencing an astounding 150% annual turnover rate.

Today’s big enterprises are rarely the enveloping, community-defining institutions from Friedman’s time, and they retain only the faintest attachment to specific physical places (or tax or legal authorities). In fact, they defy attachment to any particular community to which they might owe some kind of social responsibility.

Perhaps Friedman won after all.

Audio available

Audio available

Audio available