The 2008 financial crisis was followed by a mass exodus of investors from actively managed funds such as Fidelity into “passive” index funds such as those overseen by BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street (the Big Three). For corporations listed in the most popular index –the S&P 500 – the results have been dramatic. In 2007, the Big Three owned seven% of the average S&P 500 corporation. Today they own 22%, and in some cases more than one third. If trends continue, we might see three financial institutions owning an outright majority of the shares of hundreds of US corporations.

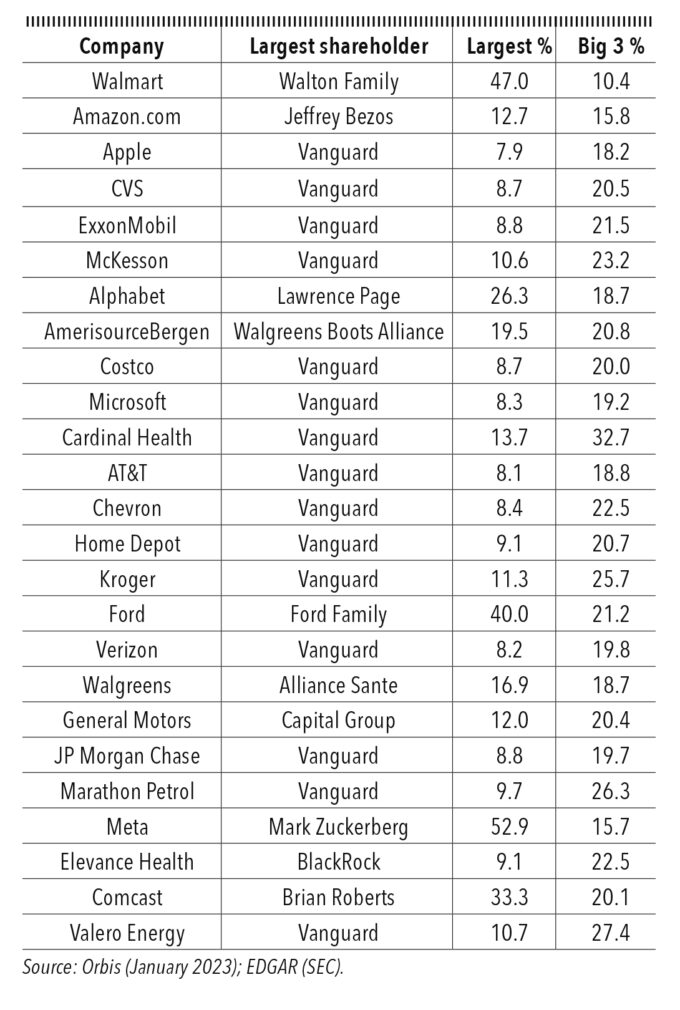

To make this concrete, the table above lists the largest shareholder for each of the 25 largest US corporations by revenues, according to data from Orbis and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). For 15 companies, Vanguard is the single largest shareholder, often including competitors in the same industry (e.g., Apple and Microsoft; AT&T and Verizon; ExxonMobil, Chevron, Marathon, and Valero). Among the largest 1,000 American corporations, Vanguard is the largest shareholder in 351.

This is something new. For nearly a century, American corporations have been known for their highly dispersed share ownership and the resulting separation of ownership and control. By 1930 nearly half of America’s 200 biggest corporations lacked a single significant shareholder, according to Berle and Means’ famous book. Today, not only do all major corporations have significant shareholders – they often have the same one.

A force for collusion, wokeness, or something else?

Now, imagine that you are the single largest shareholder of hundreds of corporations in an economy. You have no discretion over which companies you buy and sell because you follow a set of rules that compel you to own a particular set of companies forever (or until your investors abandon you). You are, in short, a universal, permanent investor: universal because you own bits of every significant listed company; permanent because you never sell, regardless of performance. How do you use your power?

One possibility might be to encourage your portfolio companies to ease up a bit on their rivalries. Fierce competition and price wars might be great for consumers, but not so much for investors, who prefer steady profits. This was, of course, the rationale for the Standard Oil Trust and many collusive schemes since.

A second possibility is that index funds could somehow join together to force corporate America to adopt a “woke” agenda that is contrary to the nation’s perceived basic values and the funds’ own fiduciary obligations. This whimsical idea has gathered a surprising constituency among several Republican politicians as well as libertarian-minded Silicon Valley types as part of a broader backlash against ESG. Texas and Florida have both pulled billions in investments from BlackRock under the pretext that the asset manager is somehow boycotting fossil fuel companies. (To be clear, BlackRock’s holdings in fossil fuels are gargantuan.)

Audio available