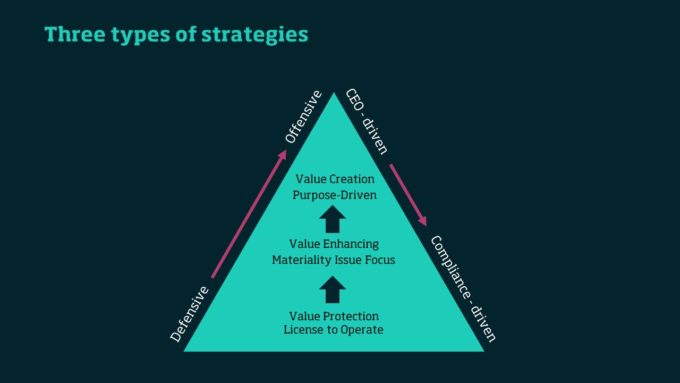

Value enhancing, risk low

The second level sustainability strategy focuses on value enhancement, which is often characterized by the combination of profitability and sustainability. Where possible, sustainability initiatives should raise profitability , either in operations or in customer-facing initiatives. Risk mitigation is a given.

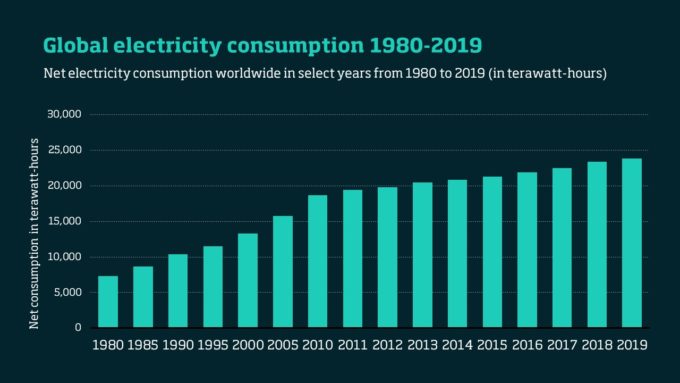

A prime example of this would be the initial efforts by Schneider Electric, a French electrical equipment group which benefited greatly from a surge in global demand for electricity. Between 1990 and 2020, worldwide demand multiplied by 2.5 times, but with a large number of people still without access to reliable power. With an increasing appetite for electricity and an ever-growing demand for non-carbon-based energy, conventional supplies were fast becoming unsustainable.

The company first responded by changing the energy sources to low carbon renewable energy, especially wind, photovoltaics, and biomass. It also focused on increased energy efficiency processes in its power plants. To enhance the value of its offer, the company also expanded into services and solutions, and created a platform that allowed consumers to manage their energy more efficiently and to be less carbon intensive. As a result of this value-enhancing strategy, sales, profits, and the stock price soared. But Schneider didn’t stop there.

In 2015, the company changed its mission statement to: “We empower all to make the most of our energy and resources, ensuring ‘Life Is On’ everywhere, for everyone, at every moment.” Over time, ambition levels rose and the Schneider sustainability impact (SSI) program – a pledge to where Schneider should be in 10 years’ time – ushered in incremental sustainability improvement initiatives while setting an ambitious target for value creation which did not seem possible at the outset.