By 2018, Interface had made all its products carbon neutral. Next, it raised the bar considerably, launching the world’s first carbon-negative carpet tiles, designed to sequester more carbon than they create from “cradle to gate” – from raw material extraction through manufacturing – without the use of carbon offsets.

Big consultancies are spotting the opportunity and making their plays. Take EY, which notes: “We’ve seen the rise of positive approaches in recent years – climate-positive, nature-positive, and net-positive business – to address our interlinked natural and social challenges. At the same time, there is growing recognition that efforts to restrain climate change and halt biodiversity loss will not be successful unless we address them together as part of a broader holistic approach.”

Regeneration, EY insists, “is a concept that addresses challenges comprehensively and provides CEOs and business leaders with a new framework for creating and protecting long-term value”. Moving beyond neutrality and zero-based frameworks, “regenerative approaches aim for complete systems changes that address the root causes of global challenges”.

When we launched our business advisory firm and think tank Volans back in 2008, in the teeth of the ongoing financial implosion, we argued the need for system change – so, yes, it’s good to see some elements of the system change agenda embraced even by full-throttle capitalists. But, caveat emptor: this is the same EY where “hundreds” of auditors were recently discovered to have cheated on their ethics exams.

True regeneration, it hardly needs saying, demands sustained commitment, ambition, and integrity even when it flies in the face of current business sense – as it often will. One interesting shift over the past decade has been the accelerating expansion of earlier discussions of the business case for change, from “Tell us why we should change!” to growing interest in evolving new business models: “How can we create new forms of value and be rewarded for them?”

The business models catwalk

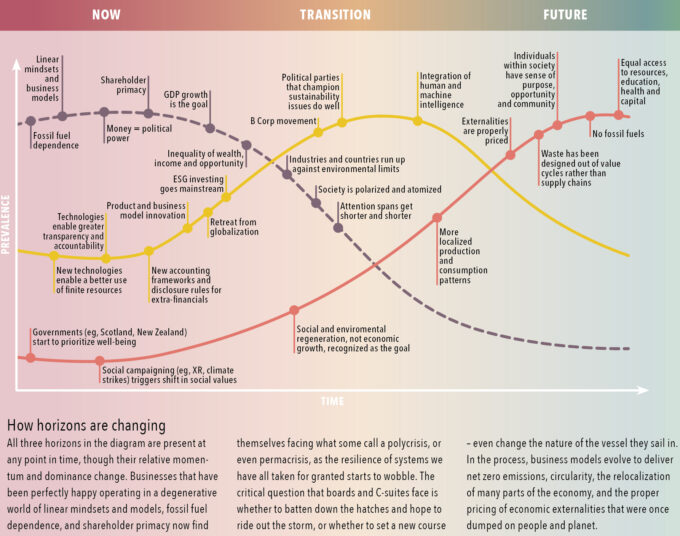

When Volans surveyed emerging breakthrough business models back in 2016, we argued that “the entire sustainability industry must undergo a radical reinvention, involving defragmentation and re-capitalization, if it is to tackle its current weaknesses, including intense siloing, internal competition, and a Babel-like confusion of terminologies”.

We spotlighted 60 business models that combined elements of the social, lean, integrated value, and circular economies, all with an eye to exponential – not just incremental – replication and scaling.

At the time, there wasn’t much research work being carried out on regenerative business models, but leading business schools are now showing greater interest. Recently, I keynoted the eighth International Conference on New Business Models, a series of events encouraging debate about and research into sustainable business models.

Audio available

Audio available

Audio available